Games Get No Respect: Rodney Dangerfield Edition

A while back, in the middle of a conversation with N'Gai Croal I mentioned we put games on a par with porn. He liked the comment and asked me to flesh it out. I knew I believed it, but I didn't really know why. I sat down and wrote a piece which N'Gai was kind enough to publish on his excellent blog . If this post seems better than the others, thank N'Gai for editing me.

So, thank you to N'Gai, and Here is the post:

I once told N'Gai that society at large perceives games much as it does porn. My reasoning is simple: everyone looks, but no one will admit it. You would be just as likely to pick up a woman in the bar and ask her to come home to see your porn collection as you would to invite her back to see your kick-ass gaming set up. The likelihood of either achieving the intended goal is very low, and one would get you slapped before she walked away in disgust. Then again, after thinking it through, I may be wrong. You may be more likely to choose porn. Applying the nine out of ten rule, nine out of ten women will say no to either proposition, but would you really rather have the one who says yes to games come home with you?

While it is easy to see the comparison, it is much harder figure out why. So when he asked me to expand on the thought and write a piece, it took me a while to figure out what to say. All I can do is talk on a personal level about a life in a career my parents don't understand and living on the receiving ends of disapproving stares everywhere from cocktail parties to school open houses.

I don't really know how we got to this point. Maybe it's because games are still considered toys. Even though most households own a game console, the vast majority of people consider videogames to be for kids. But if this misconception were the genesis of the low regard, Mickey Mouse would be mentioned in the same breadth as Jenna Jameson. He is mostly for kids, but adults don't put him in a porn box, and they are also willing to sit down and watch it with their kids. Some women may not even be offended if you asked them back to your place to see your digitally remastered "Steamboat Willie." But when it comes to games, Fox News has no qualms about backing journalist Geoff Keighley into a corner over the "Debbie Does Dallas"-meets-"Star Wars" content--content which is not even contained in Mass Effect. There must be another reason.

It could be the misconception that games are only for kids, combined with the sophisticated and sometimes violent content contained in games aimed at the average player--who happens to be 33 years old. Looking at trailers from Grand Theft Auto IV will provide no greater understanding of the feel of playing the game, or its contextual violence, than looking at a medley of death scenes from "The Sopranos" communicates the familial bond portrayed on the show. "The Sopranos" was not for kids and was not written as if it were. But if the public thought it was available on the Disney channel, they would be upset.

I think I am on to something. The majority of the public does not know what is in a game, or what goes into making one, but they still think we sell mature content to kids.

It is very easy to exist in the mainstream and never see a game. Most games sell less than one million units. A number which is the media equivalent of a hair on the back of a flea, hanging from the tip of a dog's tail. Unless you watch late night MTV, ESPN or G4, you won't see an ad for a game. Outside of comic books, Teen People and gaming publications you will never see an ad in a magazine.

If you want to buy a CD of a DVD, there is a place to buy one within walking distance of where you are sitting. Think about it, there is. If you want to buy a game, you have to mean it. You really have to look. When you walk into our number one retailer, Wal-Mart, games are hermetically sealed in glass coffins in the back of the store. I don't even know if they put the bullets behind glass. Unless you went to the store to look for one, you would not even know they exist . . . even though games are a growth area for them.

Forget about a non-gamer walking into our second-largest retailer, GameStop. There is no reason for them to go there, unless they're buying a game for someone else. If they do, they find a store that largely resembles the cluttered basement of their mother's house when they were a kid. Most of the time it does not smell much better. If they get past the front door, the counter person, whose every word is available to publishers for a price, will only discuss the last thing corporate was paid to channel through his mouth--right before he suggests you buy it used.

In other words, the mainstream has no access to what is really happening. Their only knowledge comes from the press. GTA had undisclosed sex in it! Hillary Clinton thinks games should be regulated like alcohol and cigarettes! Guitar Hero moved a lot of units! It is all their fault for not taking the time to learn about the industry we love.

Or maybe it is time to look in the mirror and realize our insular world is creating the issue. We suffer from low self-esteem without even knowing it. Like the porn business, too often we measure our self-worth by our ability to transition into to other media, or to cross over completely. Jenna Jameson is interviewed regularly by the mainstream media; she's viewed as a success not only because she sold her company to Playboy for hundreds of millions, but because she also appears in mainstream films. As a matter of fact, she achieved national press when she stood up at the AVN Awards, in front of an audience of her peers in the porn business and announced she would never appear in porn again. The announcement came as she was presenting the newly named "Jenna Jameson" crossing over award to the porn star with the best presence outside of porn.

Their biggest star is celebrated for her ability to shed the stigma of her origins and move on from the business relatively unscathed. We are not a hell of a lot different in games. Too often, we measure our self-worth by validation from industries other than our own. We see all kinds of press comparing games to box office receipts. Do you ever hear the movie industry comparing themselves to games, to television viewers, to live theatergoers? They don't, because games are nothing like box office.

We have a single window and a smaller market. We should be proud to say our margins are significantly higher and we know our consumers better. Franchises extending beyond a third installment are the rule, not the exception. We also exult in game-to-film transitions, as if the transition to film is a validation of our art. A franchise is often viewed as a success of it makes into film, but the film is completely irrelevant. We don't need the validation.

If games are so important, why won't we talk about them honestly? We just don't think they are important enough.

When I was about 13 years old I wanted a computer. Scratch that--I needed a computer. I went to my dad and told him I needed an Apple ][ (anyone who had one would only use the brackets for the "2" designation). I showed him the ad I found in a magazine and explained how I would learn how to program on this computer. What? The ad has 16 screen shots and 15 of them are games? I didn't even notice. I was looking at the command prompt for BASIC programming in the lower left corner. I could not admit I wanted it for the games.

Even at 13, I knew that games were too frivolous an application to justify the powerhouse of computing created by 16K of on-board memory and a cassette deck. The funny thing was, my dad still bought the computer; I still played games; and when I got bored, I taught myself to program. Maybe I wasn't lying. Maybe dad is just smarter than me. The truth of matter is, games turned out to be good. We both knew I was going to play them. I just knew instinctively that I couldn't admit it.

Flash forward almost exactly 20 years later. I am sitting at my desk at Eidos when I get an email--subject: "Meeting with Steve Jobs to hear about the future of computing." I almost wet my pants. I am sitting at this desk because Steve Jobs envisioned a personal computer. I responded with an immediate yes. I didn't really care what the email said, I just wanted to meet Steve Jobs; and, at least by email, he wanted to meet me. I anxiously waited for the day to arrive and found myself at Apple headquarters, sitting down to meet the man.

He led off with an Apple survey, which revealed that games were the second most popular application on consumer computers, and he wanted to support them. The survey actually surprised me. I could not believe so many people lied. Games are clearly number 1. Jobs knew it too. Because games advance technology more than any other application, with the possible exception of...porn.

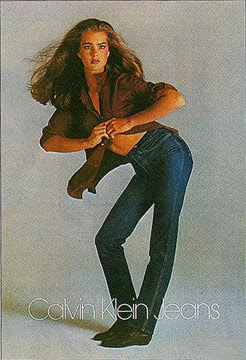

These two applications consume more bandwidth and processing cycles than any other two applications on the web today. People generally buy new technology for the most taxing applications, and in this instance, people were more willing to admit to gaming than something else. Porn may have helped the VHS beat Beta, but Jobs would only go so deep into the well. And since the greatest marketer of our time thought he needed games to get consumers back to the platform, I gave him Tomb Raider in exchange for a great marketing deal. Tomb Raider appeared prominently in the launch campaign for the iMac in 1998. The iMac ads bolstered Tomb Raider sales on all platforms. Tomb Raider told consumers that their iMac wanted to play with them.

Games were flying high. Steve Jobs was going to save Apple and he was going to put us in the forefront. He would garner mainstream attention and give us a much needed endorsement. The medium would be cast in the same light as a film from Pixar, rather than Vivid. Then I got the call from within the industry. Doug Lowenstein, who was running the ESA (then called the IDSA) called to ask for titles he could show to Congress. The ESA held annual exhibitions where they would set up videogames in front of Congress to show games were not bad. Doug asked me for a game. I offered Tomb Raider. It was the number one game on the market and best represented state of the art game technology and character.

He turned me down.

He said he could not show guns and violence to Congress and expect them to treat him favorably. Yet that same year, "L.A. Confidential," with more guns and violence than Tomb Raider, was nominated for an Academy Award as best picture. The winner that year? "Titanic," which had more nudity than any commercial videogame on the market at the time or since. Doug did more work than anyone I know to advance the cause of gamers and ensure constitutional protection for games. In his learned, expert view, he could not show Tomb Raider to a panel of mostly old white guys. He knew that his message would be rejected if he proudly displayed the best we had to offer.

That was 10 years ago, and while things have changed a bit, our industry is still young. We are just getting to the point where people will publicly admit they play games. The kids who played the first NES are growing into the adults who shape our entertainment and consumer decisions--and they still play games. We are on the cusp of genuine recognition. Once we get there, how do we define ourselves? As a young medium, people often say that the game business has not created its "Citizen Kane." The reality is, even if we had, we wouldn't know it. We have not defined a grammar for gaming or a structure for criticism. Hell, we have not even defined a uniform system of titles and credits for the people who make games. How much respect are we showing ourselves?

We must define our medium before others do it for us. Or should I say continue to do it for us? Shakespeare's plays were viewed as entertainment for the common man and not as high art. Until they were deeply analyzed, explained, and proven capable of standing the test of time. Most games, like most plays, are not Shakespeare; 99 percent or more, of everything created is absolute s--t. But there are some gems. We must figure out ways to identify those products--and elevate the people responsible for their existence.

We have many things to be proud of. Sam Houser, the most self secure man in games, once told me, "If someone can give me a single creative or financial reason to make a GTA film, I would do it." He is right. I think he said it about ten years ago and I still don't have one. Sam looks at his game as his art. His team is not setting out to make something that might tickle the fancy of their favorite filmmaker, driving that director or producer to make a movie. The team puts their collective heart and soul into their game. Their game is their statement. They take their external validation from the people who love to play their game. By working this way, their game stands alone, and their example stands a very good chance of transforming the industry.

Change is coming from the outside traditional gaming as well. I wrote a post on my blog in which I quoted the back cover of Ian Bogost's book, "Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video Games," where he wrote, "Videogames lack the cultural stature of 'legitimate' art forms because they are widely perceived to be trivial and meaningless." I was the only one who picked up the book, because the crowd of people at the TED conference felt videogames lacked any meaningful cultural stature. Bogost's first book, "Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism," is an attempt to establish a framework for review and analysis of games. "Persuasive Games" builds on these ideas and starts to explain the power of games. These books are important and are step in the right direction. They are establishing a language that will allow gamers and non-gamers alike to understand and discuss this medium. It is our responsibility to invite people into our world, and show them what they are missing.

Because the world is not going to one day wake up and proclaim that games have more value than porn.

Comments

It's not as if these parents in question are inadequate of their parenting duties, but the fact is that because the general public is ignorant to the materials inside of the videogame, they begin to expose their developing children to mature themes that the little bold letters on the lower corners of the box art heavily protests.

The portion in the article that I highlighted was one of many courses of reasoning that you took in order to ensure the validity of the main case of our industry's lack of 'cultural currency and value' that you presented with your comparison between videogames and pornographic films. I look forward to keeping up with your informed opinions about the videogame industry's relationship with our world's mass media.

Keith